Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun: Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)

Curated by Victor Wang

The High Commission of Canada in the United Kingdom

30 November - 17 February, 2018

Installation view, ‘Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun:

Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’, Canadian High Commission, Canada Gallery , London, 2018.

In response to the recent celebration of Canada’s 150 years of confederation, guest curator Victor Wang and influential contemporary artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (b 1957), who is of Hul’q’umi’num’ Coast Salish and Okanagan (Syilx) First Nations descent, present the exhibition ‘Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun: Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’.

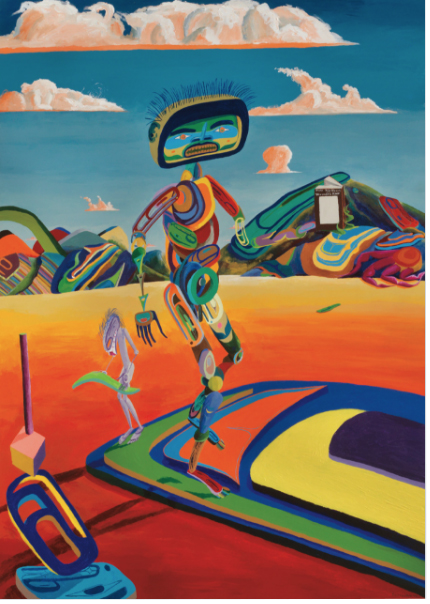

Guardian Spirits on the Land: Ceremony of Sovereignty (2000), courtesy of the artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine Art

This is the artist’s first institutional solo exhibition in Europe, and the first solo exhibition by a Canadian First Nations artist in the Canadian High Commission’s gallery in London.

For more than 40 years Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (b. 1957) has recorded issues of land rights, national identity, environmental destruction and what he sees as the real forms of colonialism facing First Nations People in Canada. Yuxweluptun was born into a family of activists, and as a pioneering contemporary artist he offers an important perspective on painting: as a space to record history from an Indigenous perspective, and as a space for resistance and opposition. Full exhibition text below.

Installation view, ‘Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun:

Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’, Canadian High Commission, Canada Gallery , London, 2018.

Installation view, ‘Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun:

Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’, Canadian High Commission, Canada Gallery , London, 2018.

Super Clear Cut (1993), courtesy of the

artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine Art

Installation view, ‘Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun:

Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’, Canadian High Commission, Canada Gallery , London, 2018.

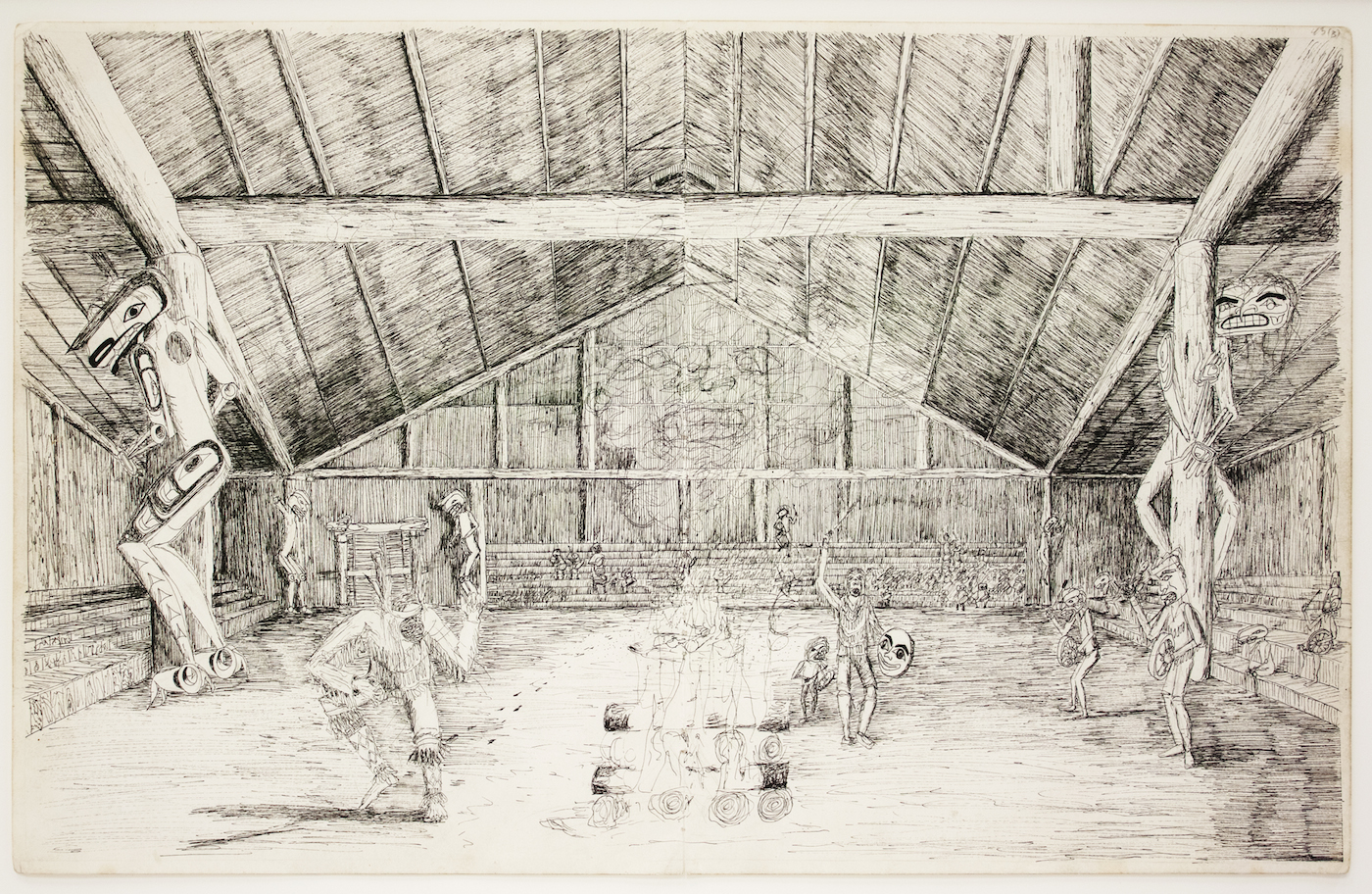

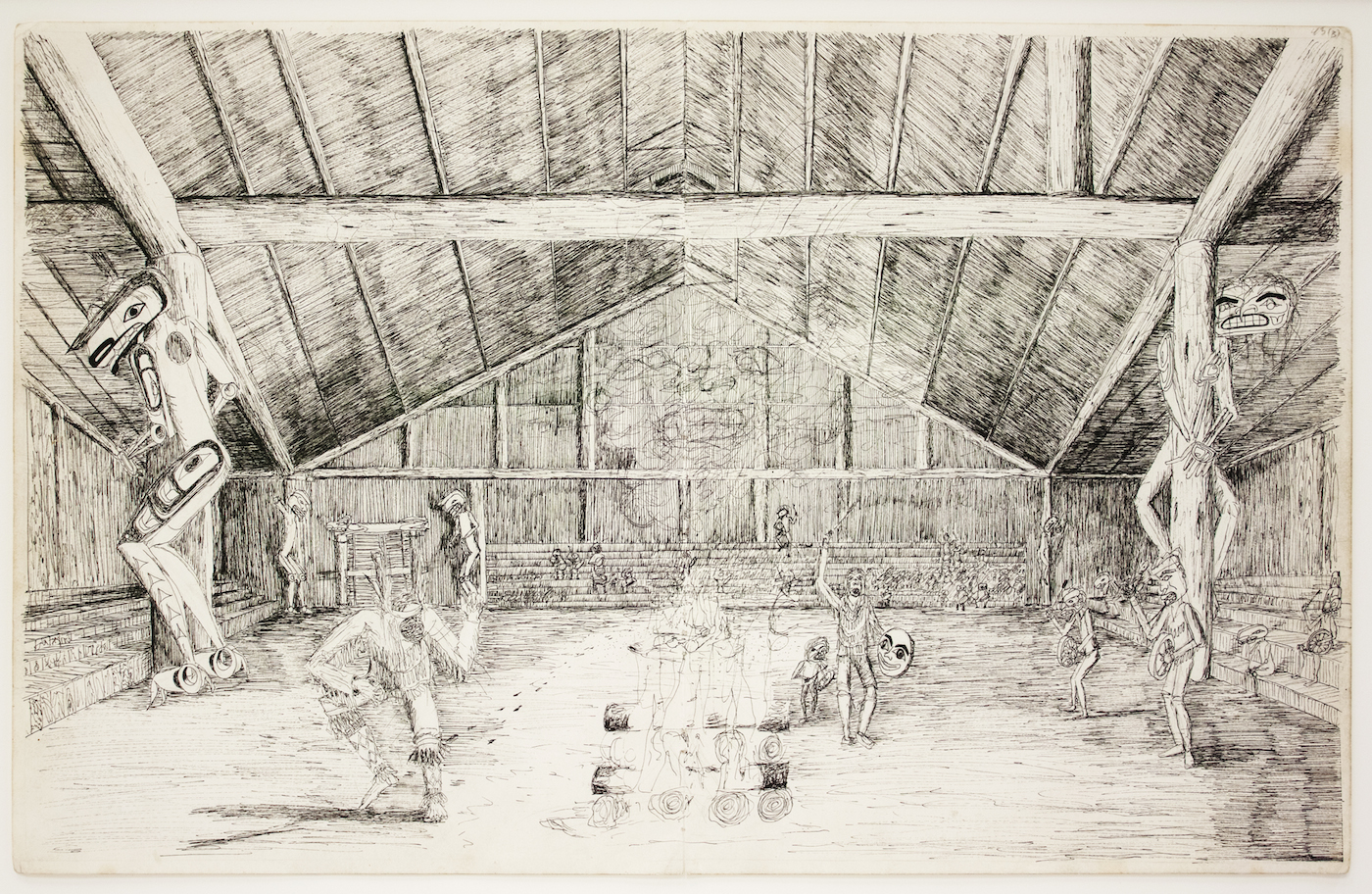

Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, Untitled Drawing - Longhouse Interior, courtesy of the artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine Art

Floor Opener, 2013

Installation view, ‘Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun:

Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’, Canadian High Commission, Canada Gallery , London, 2018.

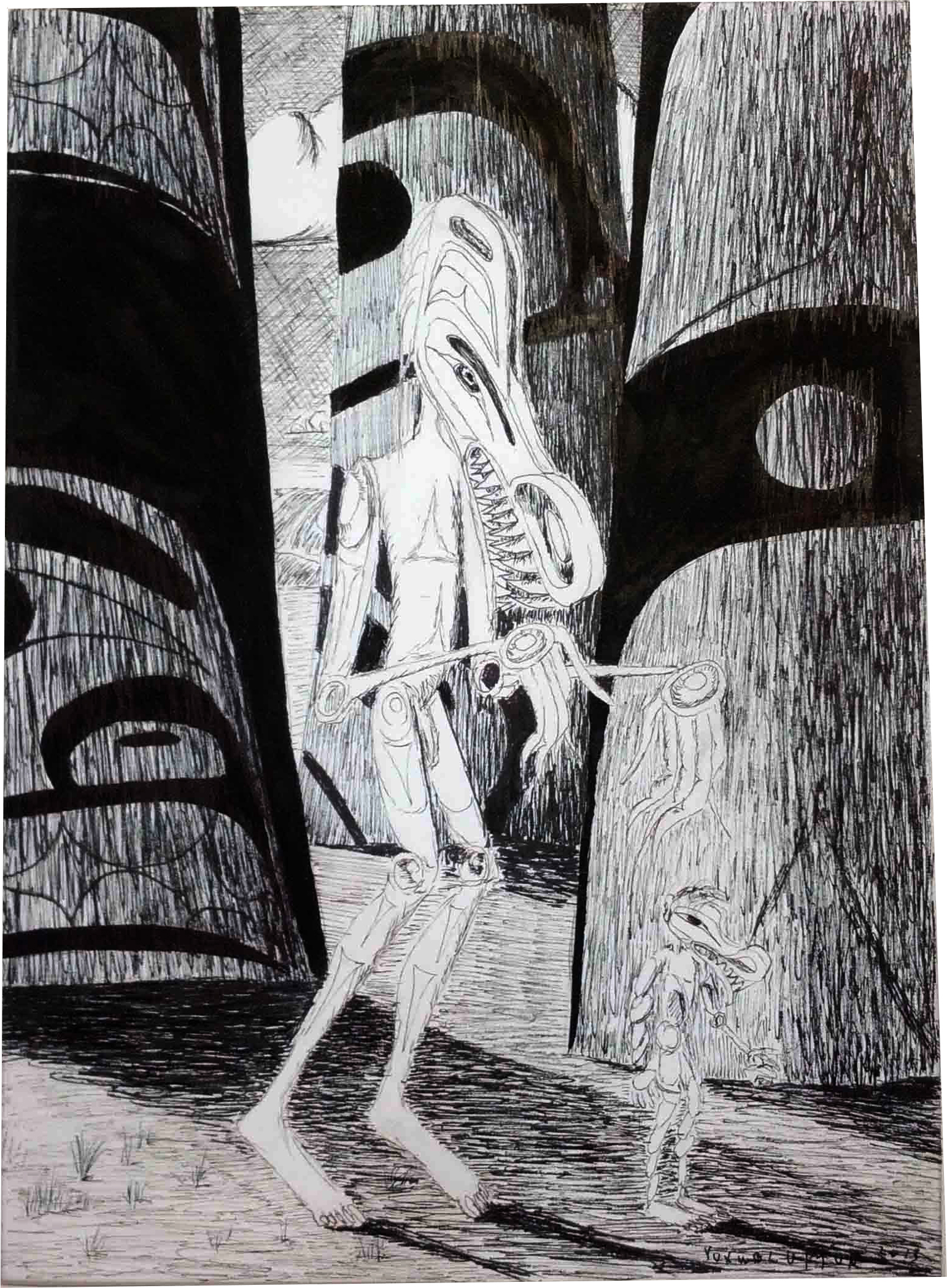

Untitled - Large

& Small Figures, 2013,

Installation view, ‘Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun:

Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’, Canadian High Commission, Canada Gallery , London, 2018.

The Intellect, 1997, Acrylic on canvas

Portrait of the artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun during installation, 2018.

Portrait of the artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun during installation, 2018.

Curated by Victor Wang

30 November - 17 February, 2018

The High Commission of Canada in the United Kingdom

Canada House, Trafalgar Square, London SW1Y 5BJ

‘Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun:

Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’

“I’m having a bad colonial day” (Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun)

In response to the recent celebration of Canada’s 150 years of confederation, guest curator Victor Wang and influential contemporary artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (b 1957), who is of Hul’q’umi’num’ Coast Salish and Okanagan (Syilx) First Nations descent, present the exhibition ‘Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun: Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’.

This is the artist’s first institutional solo exhibition in Europe, and the first solo exhibition by a Canadian First Nations artist in the Canadian High Commission’s gallery in London.

For more than 40 years Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (b. 1957) has recorded issues of land rights, national identity, environmental destruction and what he sees as the real forms of colonialism facing First Nations People in Canada. Yuxweluptun was born into a family of activists, and as a pioneering contemporary artist he offers an important perspective on painting: as a space to record history from an Indigenous perspective, and as a space for resistance and opposition.

The exhibition, on one level, draws attention to the entangled connections between unceded First Nations territories in Canada (those lands that were never signed away through a treaty process or conquered by war) and the displacement of Indigenous people, both in representations of landscape art and in Canadian (art) history. On another, how Yuxweluptun’s practice opens up questions about the institutions that are designated to record history, and how communities existing outside of those institutions struggle to document and shares stories of trauma to future generations.

The title of the exhibition, ‘Time Immemorial (You’re Just Mad Because We Got Here First)’, a whimsical remark about the idea of Canadian confederation, and the exhibition itself, points to a concept of a time and history before European contact – to communities and civilisations that existed long before Europeans began to exercise dominion over First Nations territories. A time immemorial: that is, a time that exists outside of the European definition of a colony, a country, a confederation and the very concept of modern Canada.

Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, Untitled Drawing - Longhouse Interior, courtesy of the artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine Art

The exhibition includes works from the 1980s to the 2000s, including the artist’s pen on paper works such as White Man Speaks with Forked Tongue, Land Claims Consultant #1 (2013), a work that speaks to the ongoing struggles with governments by Indigenous peoples to have their land titles recognized, and the difficult task of having pre-European rights and interests properly represented in modern common law. Where traditional land ceremonies and Indigenous forms of recording history are not recognized under the Canadian court system. The work is part of an ongoing portrait series, Super Predator, that often depicts animated humanoid-like creatures wearing business suits.

White Man Speaks with Forked Tongue, Land Claims Consultant #1 (2013), courtesy of the artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine Art

White Man Speaks with Forked Tongue, Land Claims Consultant #1 (2013), courtesy of the artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine ArtAlso featured is the work Guardian Spirits on the Land: Ceremony of Sovereignty (2000), a painting that adopts traditional Northwest Coast and Coast Salish cultural myths and traditions to depict a ceremony of sovereignty, conducted by the guardian spirits of the land. The work addresses the need for sovereignty on unceded First Nations territories, and the important connections these traditional lands have with the history of a people and the ceremonies that have been practised for thousands of years.

Yuxweluptun reimagines the ‘white’ and ‘traditional’ twentieth-century Canadian landscape – notably void of any depiction of First Nations – to remind his audience that these landscapes were not, in fact, ‘untouched’ before the arrival of European settlers. The artist is not only speaking to the physical absence of First Nations people in the scenes portrayed, he is reminding us of their absence from our institutions and wider contemporary society. Yuxweluptun’s use of vibrant colours and current themes imagined through the protagonist in his paintings abstract his work beyond a simple application of traditional Northwest Coast forms and histories, and into a new complex interwoven space of ancestry and the recording of an Indigenous contemporaneity.

Guardian Spirits on the Land: Ceremony of Sovereignty (2000), courtesy of the artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine Art

Guardian Spirits on the Land: Ceremony of Sovereignty (2000), courtesy of the artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine Art

Nature (its destruction through industrialization); the environment, as both subject and ancestral being, and the complex issue of land rights and control over natural resources in Canada are both a personal and a collective subject matter which play a central theme in Yuxweluptun’s art. Super Clear Cut (1993), for example, depicts the aggressive clearcutting of forest in British Columbia, and the destructive effects this industrial practice has on the local ecosystem and natural habitats. Yuxweluptun also points to the significance of the landscape to First Nations history and memory. Nature, for Yuxweluptun, is a living entity that should be protected, and his landscapes regularly mirror the appearance of his protagonist, making visible the interconnections between nature and community. Often depicted through a mix of human traits and qualities, the landscape is repeatedly stylized with traditional Northwest Coast masks, characteristics and forms. The protagonist in Super Clear Cut, also wearing a stylized traditional mask (like the leaves on the tree), is shown watching over the only tree that was left uncut.

Super Clear Cut (1993), courtesy of the

artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine Art

Super Clear Cut (1993), courtesy of the

artist and Macaulay & Co. Fine Art

Yuxweluptun’s work occupies a complex space that interweaves pre-and post-colonial ways of life, questioning legacies of landscape art, Canadian history and Surrealism by recontextualizing traditional Northwest Coast forms and myths to bring to light what Yuxweluptun sees as the source of its origins, and subjects that have always been part of Indigenous culture. The artist’s work serves as both an artistic expression and also as a journal. Through these pieces, he documents the experiences of Indigenous communities and communicates with them. They also serve as an at-times blunt refusal to accept the dominant narratives of how First Nations peoples are portrayed by the ruling powers and their institutions. Presented in the context of Canada House, the exhibition questions how the history of colonization in the United Kingdom is understood when confronted by indigenous contemporary practices (from the former British colonies), and the importance of remembering that First Nations peoples are not merely absent in art; their stories and histories – their very existence – have been buried not just in art history, but also in world history.

Text by Victor Wang

Publication

Interview

The Art Newspaper, Podcast epsiode ten: restoring Iraq’s heritage, plus the complex politics of First Nations art

VICTOR WANG

All content property of © Victor Wang 2009 - 2024 All rights reserved -- BEIJING - LONDON.

All content property of © Victor Wang 2009 - 2024 All rights reserved -- BEIJING - LONDON.