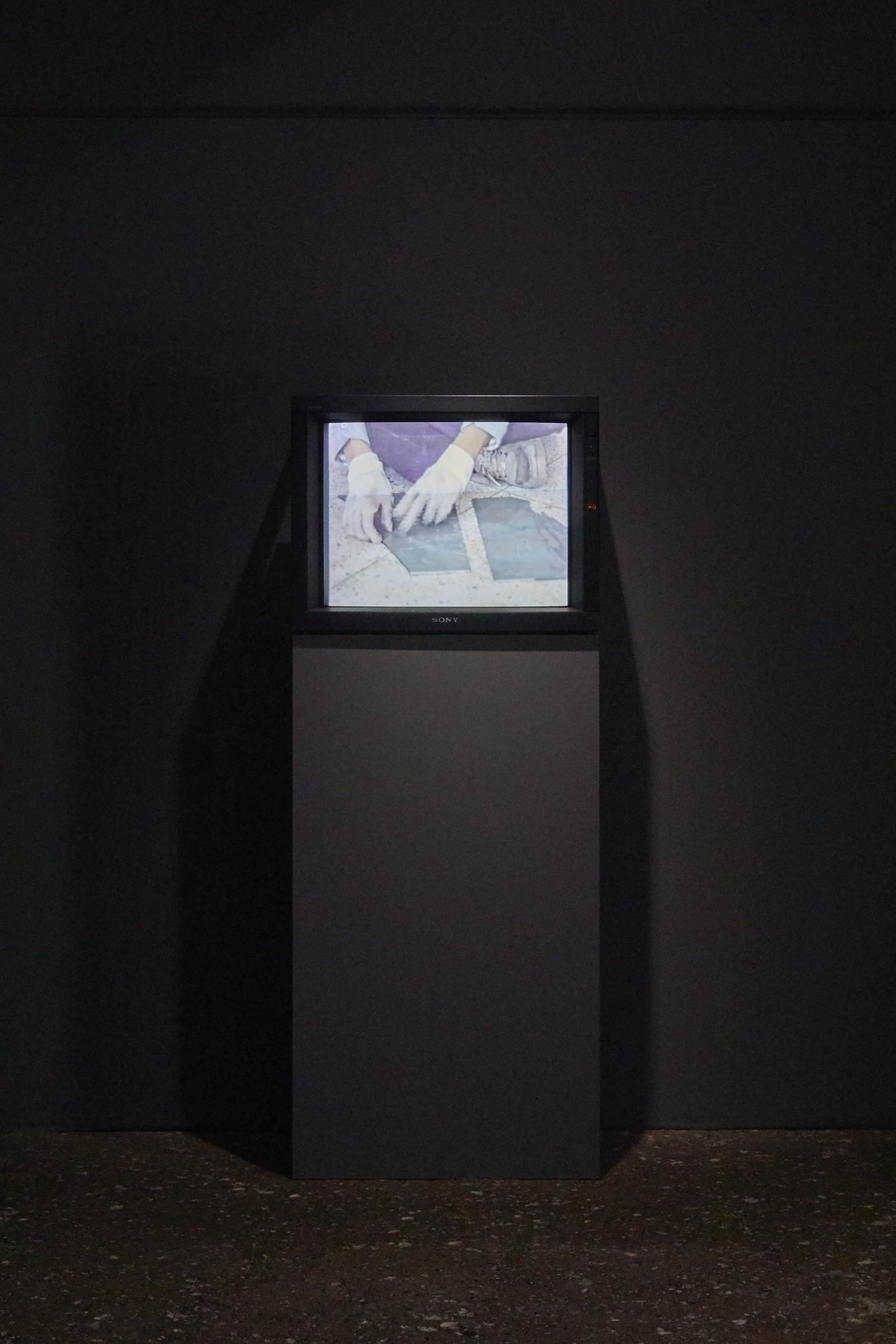

Gallery 1, ZHANG Peili,

installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo, photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

Gallery 1, ZHANG Peili,

installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo, photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo

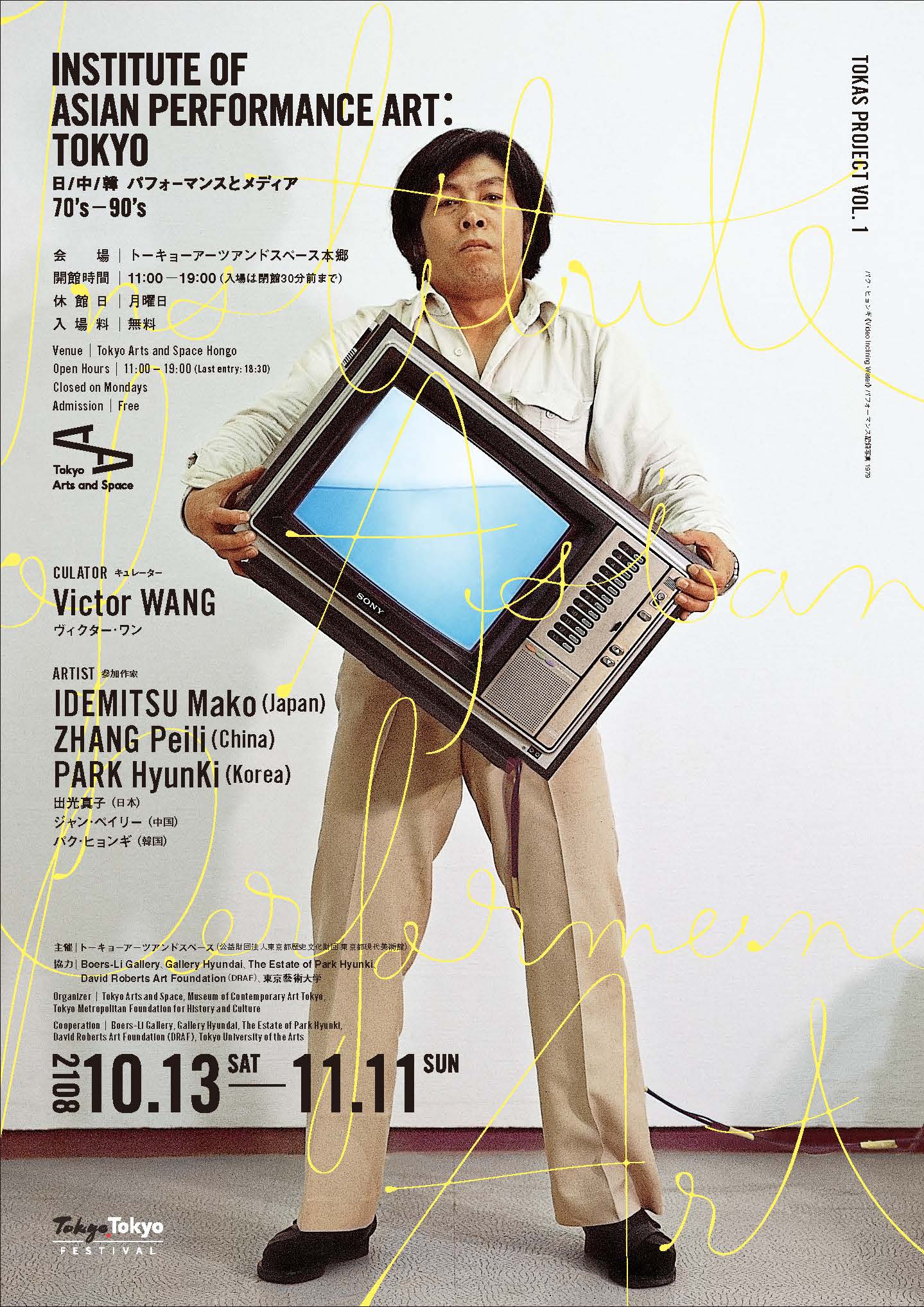

TOKAS Project Vol.1

日/中/韓パフォーマンスとメディア 70's - 90's

Artist:IDEMITSU Mako 出光真子 (Japan) | ZHANG Peili ジャン・ペイリー (China) | PARK Hyunki パク・ヒョンギ (South Korea)

Curator: Victor WANG ヴィクター・ワン

Organize:Tokyo Arts and Space トーキョーアーツアンドスペース本郷

(Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture)

Cooperation:Boers-Li Gallery, Gallery Hyundai, The Estate of Park Hyunki, Tokyo University of the Arts, David Roberts Art Foundation (DRAF)

Venue:Tokyo Arts and Space Hongo

Date:2018.10.13 - 2018.11.11

The Institute of Asian Performance Art (IAPA) has entered into a collaboration with Tokyo Art and Space (TOKAS) in Tokyo to conduct a study on the influence of Asian artists on the evolution of video as an art form. The research will focus on the experimental techniques employed by pioneering video artists from China, Korea, and Japan during the 1970s to 1990s.

Video art is a medium that embodies both material and immaterial qualities. Its genealogy is complex and has spawned numerous branches and parallels around the world, with characteristics and beginnings that often connect it more appropriately to the other temporal arts of music, performance, dance, theatre, and cinema.[1] As the medium and format of video art are intimately linked to technological advancements that do not originate from the European art-historical tradition or an identifiable critical discourse as an art medium, artists from Japan, Korea, and China have been able to cultivate and refine their own distinctive aesthetics and methods of video production outside of a Western narrative, and in vastly dissimilar political and societal contexts.

ZHANG Peili , ‘Unertain Pleasure II’ , 6 channel, 12 screen video installation, 1996. Installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

ZHANG Peili , ‘Unertain Pleasure II’ , 6 channel, 12 screen video installation, 1996. Installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

ZHANG Peili , 30x30 , single channel video, (32'9") 1988,

installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo

installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo

Divided into three solo presentations between the three TOKAS Hongo galleries, the exhibition looks at the inter-regional dialogues occurring in East Asia, and the unique approaches to the medium that were developed by pioneering artists Park Hyun-Ki, Zhang Peili, and, Mako Idemitsu.

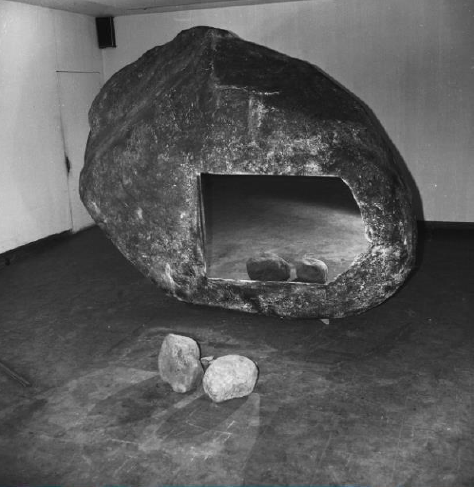

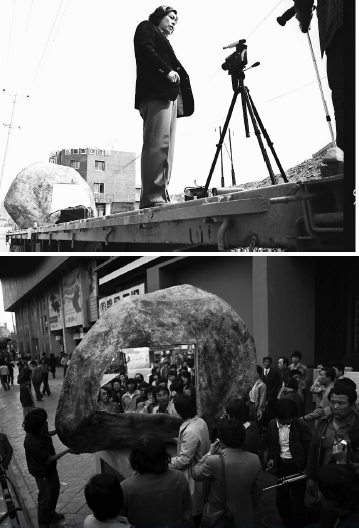

Influential Korean video artist Park Hyun-Ki not only helped to introduce video art to the local Korean art scene [2]but also developed a distinctive body of work that incorporated performance, and sculpture, informed by Eastern philosophy and culture. This includes pieces such as Media as Translators 1982, both a performance and installation in nature, the event removed the domestic television from its usual setting and incorporating it into an outdoor event lasting several hours that subverted its commercial function while confronting ideas of ritual, landscape, de-materiality and Minimalism from a Eastern context. Examining a type of fluidity between nature and technology. In Video Inclining Water, (1979), performed for the 1979 São Paulo Biennale, Park tilted a video monitor displaying an image of water in different directions to give the illusion that the monitor was filled with water. Moving between image, site, nature and body, monitors were often used as performative devices and as material, as extensions of the medium and the content displayed, to be incorporated both within the white cube and outside of it.

ZHANG Peili , 30x30 , single channel video, (32'9") 1988

Installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

ZHANG Peili, Personal Hygiene , 3 channel video; 3 monitors, pilled up (5'49"), 1998

, installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo

The rise of portable video technology in the 1960s and ’70s in Asia, such as the introduction of the Sony ‘Portapak’ in 1967-8 and the development of the VHS format, was key in placing the tools of the medium in the hands of the artists and cultural producers in the region. In the case of China, even without a developed art market or much interrelation with Euro-America, artists had been producing video works years before Western video art was ‘systematically introduced to China…in 1992’.[3]Prior to this time there were strict entry regulations in force in China in relation to foreign media and art content.

Zhang Peili, considered as the first Chinese artist to work in video, manipulates viewpoint and framing, and in particular a sense of time, to create unconventional recordings of repeated specific banal actions, such as breaking glass, washing and shaving or scratching oneself, over long durations or looped across several monitors. Peili was an early proponent of conceptual art in China, and works like 30x30 (1988), widely recognised as the first work of video art by a Chinese artist, have at their centre an investigation – through the meticulous and monotonous task of repeatedly breaking a 30-by-30-centimetre mirror, and gluing it back together – into a complex form of time manipulation through video technology. Which also, in part, asks questions about the performative function in early video art. In speaking about the work Peili says that he “wanted to do something and say something about video, but I felt that I was also doing a performance”. The work is a recording of a live event with no audience, an approach that he describes as being both “video and performance”.[4]

Gallery 2, IDEMITSU Mako, installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

Pioneering Japanese artist Mako Idemitsu is often credited as an ‘important precursor to feminist art in Japan’.[5]Experimenting with film and video art since the 1970s, Idemitsu often examines the domestic as gendered space in Japanese society, for example in her work ‘Another Day of a Housewife’, 1977, the home, becomes a site of domestic labor and physiological suppression of Japanese women. Often in her video works a television monitor is present as a symbolic subjectivity, or external protagonist, watching as the housewife performs daily tasks. Works such as ‘The Marriage of Yasushi’, 1986, explore how the personal, and the private space within Japanese households set the stage for family dynamics and the interrelationships between, for example, mother and son, wife and husband, and the division of labor based on gender to be formulated and reinforced. Works such as these also comment on a specific social condition that has developed in Japan since the mid-1960s, one that has simultaneously functioned as both a ‘domestic support unit’ that has helped sustain the expansion and high growth of the economy in Japan[6], while dividing the labour roles between men and women in society.

Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

IDEMITSU Mako, ‘Another Day of a Housewife’, video (9'50"), 1977 , Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo

In contrast, by moving between the practices of artists working in video in Asia, in the cultural sphere Asian video histories are increasingly being recognised as a networked constellation of social, political, economic, technological and historical concerns and relations, meeting and weaving together at different points and times to construct a wider dialogue and links within the region, often confirming unique origins and approaches to the medium, offering new ways of connecting these histories and practices with the wider world.

Gallery 3, PARK Hyunki, installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

PARK Hyunki,’Video Inclining Water’, photo documentation of the performance, 1979, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo, photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

PARK Hyunki, ‘Media as Translators’ , photo documentation (June. 26-27, 1982), 1982, installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

PARK Hyunki, ‘Media as Translators’ , photo documentation (June. 26-27, 1982), 1982

PARK Hyunki,‘Pass Through the City’ , film documentation, 1981, installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

![]()

PARK Hyunki,‘Pass Through the City’ , film documentation, 1981, installation view, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

![]()

PARK Hyunki,‘Pass Through the City’ ,documentation, 1981

PARK Hyunki,‘Pass Through the City’ ,documentation, 1981

PARK Hyunki,‘Pass Through the City’ , film documentation, 1981, Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo , photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy: Tokyo Arts and Space, 2018

Institute of Asian Performance Art: Tokyo

TOKAS Project Vol.1

Artist:IDEMITSU Mako (Japan), ZHANG Peili (China), PARK Hyunki (South Korea)

Curator: Victor WANG

[1] Chris Meigh-Andrews, A History of Video Art, Part 1, 2nd. edn. (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014).

[2] National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea Press release, ‘Park Hyun-Ki Mandala’, January 27–May 25, 2015, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea” (Korea: NMMCA, 2015)

[3] Barbara Pollack, ‘Breaking and Entering: In His Videos, Zhang Peili Destroys and Restores to ‘Capture and Emphasize Time”’, ARTnews (5 May 2017).

[4] Pollack.

[5] Norio Nishijima, ‘Myth of the Heart: The Film and Video World of Mako Idemitsu’,http://makoidemitsu.com/myth-of-the-heart-by-norio-nishijima/?lang=en, accessed April 12, 2018

[6] Hiroko Hagiwara, ‘A Bright, Shiny, Fabricated Family Life Mothers, Sons, and Daughters in the Work of Mako Idemitsu’, http://makoidemitsu.com/a-bright-shiny-fabricated-family-life/?lang=en, accessed April 18, 2018

「インスティチュート・オブ・アジアン・パフォーマンス・アート(IAPA):東京」では、トーキョーアー

ツアンドスペース(TOKAS)との共同で、芸術形式としてのビデオがアジアのアーティストにもたらし

た影響、そして中国や韓国、日本の先駆的なビデオアーティストたちが1970 年代から1990 年代にか

けて行った種々の実験的なアプローチを探る。

いわゆる「ビデオアート」と呼ばれるものの技法や系譜には、世界中に多くの系統や類型があり、そ

の特徴や始まりはたいていの場合、音楽やパフォーマンス、ダンス、演劇、映画など他の時間芸術とつ

ながっている1。

ビデオアートの技法と形式は、技術の進歩に直結しており、西洋の美術史的伝統や、特定可能な

言説に根ざした芸術技法ではない。そのため、日本、韓国、中国のアーティストたちは、西洋の文脈の

外から、多様な政治的、社会的状況のなかで、ビデオ制作に対する型にはまらない独自の美学とアプ

ローチを展開し、形作ることができた。

TOKAS 本郷で実施する本展覧会では、東アジアにおける地域間の対話と、パク・ヒョンギ、ジャン・

ペイリー、出光真子らの先駆的なアーティストたちが発展させた技法に対する独自のアプローチに着

目する。

影響力のある韓国のビデオアーティスト、パク・ヒョンギは地元・韓国のアートシーンへビデオアー

トを紹介しただけでなく2、東洋の哲学や文化に基づくパフォーマンスや彫刻と一体化させた特徴

的な作品を作り出した。パフォーマンスとインスタレーションに自然を取り入れた作品《Media as

Translators(翻訳者としてのメディア)》(1982 年)では、通常、家の中にあるテレビを、数時間にわた

り屋外に持ち出すことで商業的な機能を覆した。そして、東洋的な文脈に基づく儀式や風景、脱物

質主義、ミニマリズムの思想に向き合い、自然とテクノロジーの間に存在するある種の流動性につい

て考察した。

1979 年のサンパウロ・ビエンナーレで発表された《Video Inclining Water(ビデオ 傾く水)》で、パク

は水の映像が映し出されているビデオ・モニターを様々な方向に傾け、モニターに水が溢れていると

いう錯覚を起こさせるようなパフォーマンスを行った。映像と場所、自然、体の間を行き来させなが

ら、パクはモニターを表現装置や素材として、あるいは技法の延長や展示コンテンツとして、ホワイト・

キューブの内外で用いた。

1967 ~ 68 年のソニー・ポータパックの登場やVHS 方式の開発など、アジアにおける1960 年代から

70 年代のポータブル・ビデオ・テクノロジーの台頭は、この地域のアーティストやクリエーターたちが

媒体となるツールを手に入れるきっかけとなった。中国では、発達した美術市場も、欧米との相互関

係にも乏しい状況の中、アーティストたちは西洋のビデオアートが「1992 年に体系的に中国に紹介

される」より何年も前から、ビデオ作品を制作していた3。それ以前の中国では、外国のメディアや美

術作品に関して、厳しい導入規制が敷かれていた。

ビデオを扱った最初の中国人アーティストとされるジャン・ペイリーは、視点や画面構成、とりわけ

時間の感覚を巧みに操り、ガラスを割ったり、体を洗ったり、ひげを剃ったり、引っ掻いたりといった

特定のありふれた動作の反復を、長時間または複数のモニターで連続するという、慣習にとらわれな

い映像撮影を行う。

また、ジャンは、中国におけるコンセプチュアル・アートのパイオニアであり、中国人アーティストに

よる初のビデオアート作品として広く知られている《30x30 》(1988 年)では、30 センチ四方の鏡を

繰り返し割り続け、それを貼り合わせて戻すという緻密で単調な行為をとおして、ビデオ技術によっ

て複雑な時間操作の形を探求した。ある意味では、初期のビデオアートにおけるパフォーマンス機能

への問題提起とも言える。作品ついて、ジャンは、「ビデオについて何かをしたり、何かを言ったりし

たかったのだが、自分がパフォーマンスをしているという感覚もあった」と語っている。作品は観客の

いないライブイベントの記録であり、自身が「ビデオとパフォーマンス」の両方であると述べるアプロー

チなのだ4。

出光真子は、「日本におけるフェミニスト・アートの重要な先駆者」と評価されている5。1970 年代

から映画やビデオアートの実験的な作品を制作していた出光は、日本社会でジェンダーの影響が大き

い場所として、家庭を取り上げている。例えば、《主婦の一日》(1977 年)では、家庭は、日本女性にとっ

ての家事労働と生理的抑圧の場になっている。彼女のビデオ作品では、テレビのモニターが象徴的な

主体として登場したり、主婦が日々の仕事をこなす様子を見ている外部的な主役としてしばしば登

場する。《やすしの結婚》(1986 年)では、日本の世帯のなかで個人の私的な空間が、どのように家族

の力学の下地となっていくのか、例えば母と息子、妻と夫のような相互関係、あるいはジェンダーに基

づく労働分担が、どのように定められ、凝り固まっていくのかを探っている。これらの作品は、1960 年

代半ばから形成されてきた日本特有の社会情勢―「家庭の単位」が日本の経済発展と高度成長を支

えてきた一方で、社会において男女間で労働の役割を分けたこと―に対する意見表明でもある6。

ビデオアートはテクノロジーに大きく依存する技法であり、地域の流通や発展、制作施設や設備へ

のアクセスが多様なため、特に歴史を整理するのが難しく、アジアに関する美術論上での「モダニズム」

や「現代性」の議論では複雑な疑問が生じる。

一方で、アジアでビデオ作品を作るアーティストたちの実践を行き来することにより、アジアのビデ

オ史は、社会的、政治的、経済的、技術的、歴史的な関心や関係によってネットワーク化された一群

として、文化圏においてますます認識されるようになっている。様々な場所と時間に出合い、組み合

わさることで、地域内でより幅広い対話や連携が築かれる。そこには独自の起源や技法へのアプロー

チがあり、これらの歴史と実践をより広い世界に繋ぐ新たな道が生まれる。

註

1 Chris MEIGH-ANDREWS, A History of Video Art , Part 1, 2nd edn. (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014).

2 National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea Press release, ‘Park Hyunki Mandala’,

January 27-May 25, 2015, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (Korea: NMMCA, 2015).

3 Barbara POLLACK,‘Breaking and Entering: In His Videos, Zhang Peili Destroys and Restores to“Capture and Emphasize

Time ”’, ARTnews (5 May 2017).

4 POLLACK.

5 西嶋 憲生「心の神話 出光真子の映像世界」

(http://makoidemitsu.com/myth-of-the-heart-by-norio-nishijima/?lang=en,accessed April 12, 2018 )

6 萩原 弘子「白々と明るいつくりものの家庭 ― 出光作品の母・息子・娘 」

(http://makoidemitsu.com/a-bright-shiny-fabricated-family-life/?lang=en,accessed April 18, 2018)

VICTOR WANG

All content property of © Victor Wang 2009 - 2024 All rights reserved -- BEIJING - LONDON.

All content property of © Victor Wang 2009 - 2024 All rights reserved -- BEIJING - LONDON.